Szymon's Zettelkasten

Powered by 🌱Roam GardenP: Everything is relative

Keywords:: PermanentNote makePublic

Reference:: R: Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely

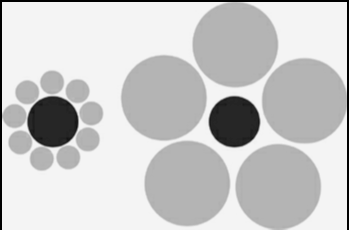

These two black circles are of the same size. Don't believe me? Measure it with a ruler.

And what's strange is, even when you know they're the same size, they don't seem that way.

This picture alone should sufficiently highlight our inclination towards relativity.

We judge things through comparison. We assign things to categories and judge them within them.

We judge the price and the taste of a coffee compared to other coffees; we don't compare it to orange juices. We don't know whether something is expensive—unless we can compare its price to something similar. We don't know if something is big—unless we ask "compared to what?" We don't know what sport (if any) we want to train—until we see a great athlete on TV (i.e., "I wanna be like Mike"). We don't know whether we're rich—unless we hear how much our friends are making. And so on...

Choices paint boundaries that help us navigate through reality—"like an airplane pilot landing in the dark, we want runway lights on either side of us, guiding us to the place where we can touch down our wheels." [Author's quote]

PN: Saying YES to almost everything: That's why trying new things is so great. It expands your horizons—you have more things to compare, so the boundaries of your reality grow.

This is why putting the most expensive dishes on a menu boosts the restaurant's revenue—even when no one buys them. Why? Generally, people will buy the second most expensive dish (because it won't look as expensive relative to the most expensive one). The highest-priced entrance acts as a guiding reference to the customer like runway lights do to the pilot who's landing the plane.

And this notion isn't limited to physical objects like food, cars, watches, and spouses—but it's also true for abstract things like experiences, emotions, points of view, etc.

Furthermore, we prefer things that are easily comparable—and avoid things that cannot be compared easily. So, if you want to be perceived as more attractive at a party, take a similar-looking friend.

Is this because the micro-comparison between two similar things boosts the winner of that comparison in relation to the third less similar?

This propensity towards relativity has interesting consequences. TK P: The consequences of our propensity for relativity

Relevant notes (PN: )/questions (Q:):

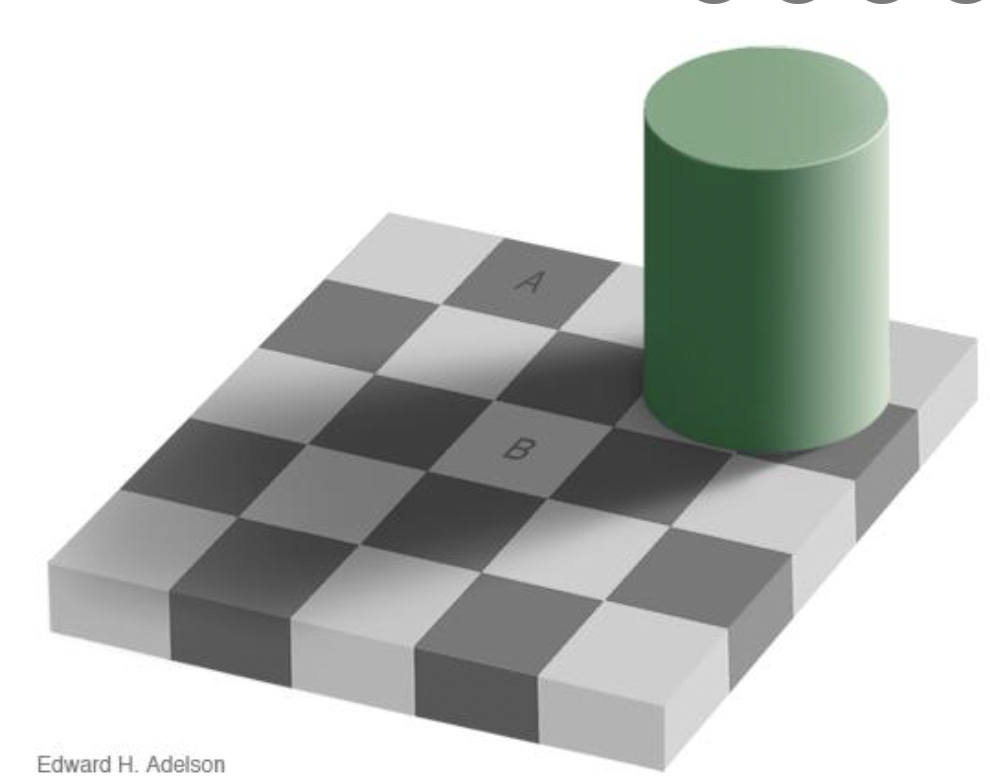

Want another visual example that highlights our irrationality? Look at the picture below. Square A and B are of the same color. (That one is even harder than the one with the circles.)

P: The first times are disproportionally powerful (anchoring): we relate things to the first experience more strongly.